Keeping

New Mexico Enchanted

We strive to create a future that supports a livable planet and just society through education and outreach, public policy advocacy, and mobilizing people to take action.

350 New Mexico Speakers Series

Rethinking Housing for a Fossil Fuel-Free Future

Speaker: Joaquin Karcher, Zero Energy Designer and founder of zeroedesigns, Taos, NM

When: Monday, March. 23, 2026 6:30 pm Zoom. Register here.

Description: This talk explores practical, cost-effective pathways to decarbonized housing, focusing on fossil fuels free construction and a new building-science–based approach capable of reducing heating and cooling energy use by up to 90%. It will briefly look in the rear-view mirror at how we arrived at today’s building practices, outline the current state of the art in high-efficiency construction, and explain how these systems work in practice. From there, Joaquin will introduce an emerging approach that simplifies high performance while dramatically cutting energy demand—offering a realistic path toward climate-aligned housing that remains attainable and cost-effective for everyday communities.

Joaquin Karcher‘s work over the last 35 years has been driven by a commitment to sustainable design, from earth architecture to passive solar/adobe construction to Passive House standards and beyond. He designed the first certified passive house in New Mexico, co-authored the New Mexico Earthen Materials Building code which was adopted internationally and has designed homes in Germany, New Mexico, Arizona and the Navajo Nation. His focus now is on affordable, zero-carbon, ultra-efficient residences powered entirely by solar energy. Karcher Biography zeroedesign website

Presented by 350NM and the New Mexico Solar Energy Association

Zia symbol is used by permission of the Zia Pueblo.

Getting ready to apply for Federal and State electrification tax credits? See our tax tips here.

Getting ready to apply for Federal and State electrification tax credits? See our tax tips here.

The Walking School Bus

Speakers: Kelly Davis Ami, Wilson Middle School Community School Coordinator and Leah Garcia, Whittier Elementary School Community School Coordinator

When: Monday, Feb. 23, 2026 6:30 pm Zoom

Register here.

Description: 350NM is excited to welcome 2 leaders of the APS Walking School Bus Program. This is a great example of climate actions with Multiple benefits. A WIN-WIN-WIN for

*APS students safety and attendance,

*the larger community and

*the climate.

The organizers share their experience of adapting the National Walking School Bus Program to Albuquerque’s International District middle and elementary schools.

Story on Walking School Bus program at Whittier Elementary and Wilson Middle School

Past Speakers Series Talks

***Events are Free and Open to the Public***

Zia Symbol by permission-Pueblo of Zia

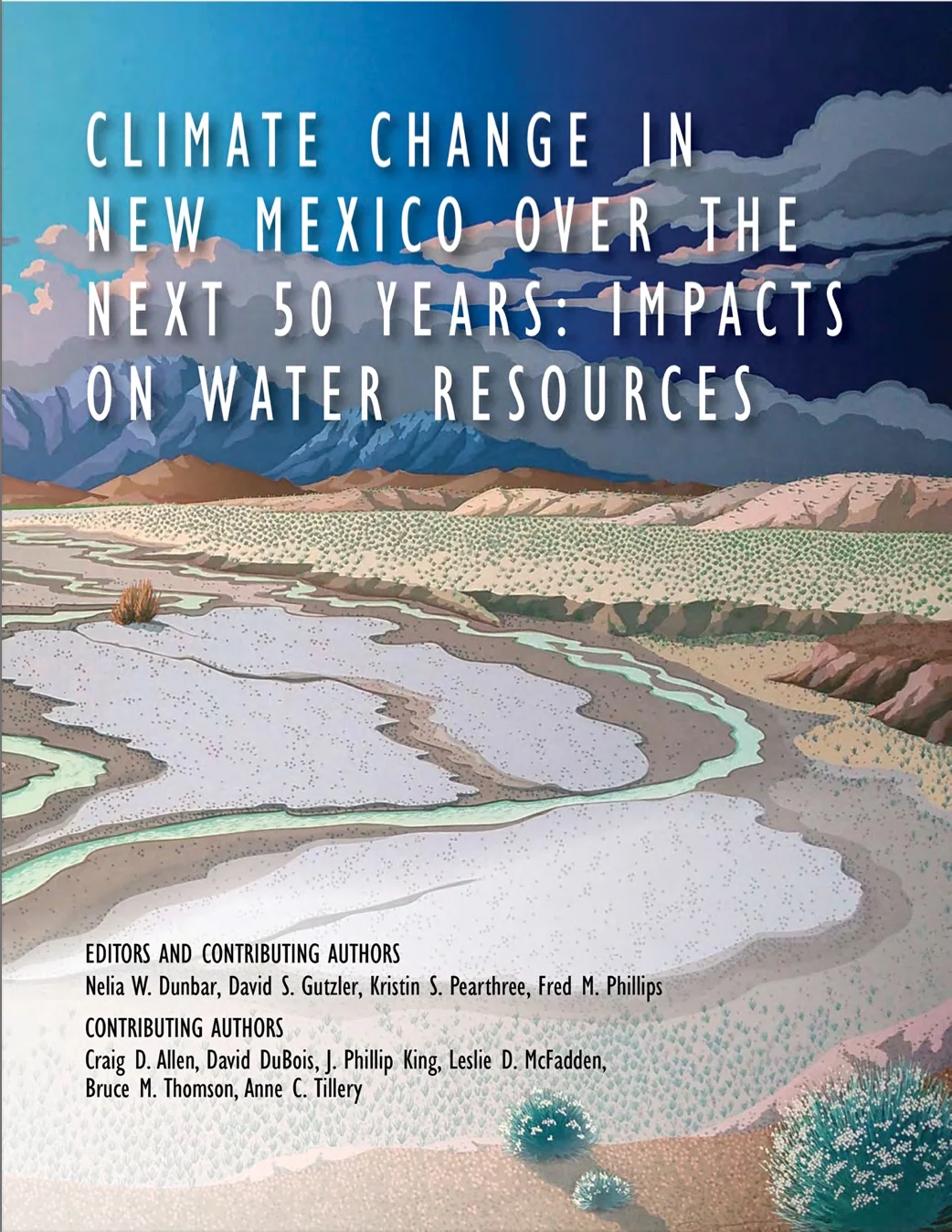

Climate Crisis in New Mexico

“New Mexico’s climate is getting hotter and drier, driven by regional and global warming trends. This means earlier springs, hotter summers, and less predictable winters. Precipitation patterns are also changing, with more intense droughts and a greater proportion of precipitation falling as rain rather than snow.” Union of Concerned Scientists

Less water for all even if precipitation is the same over the next 50 years

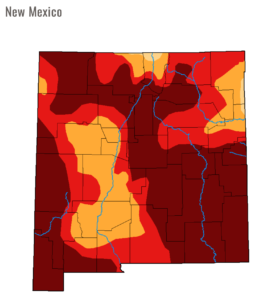

The March 2022 Leap Ahead Analysis provides the most comprehensive overview of New Mexico climate aridification and its impact on water and landscape through 2070. Temperatures are expected to rise by 5 to 7 degrees F. Rising temperatures are already reducing snowpack, streamflows and groundwater recharge (projected decline of at least 25%) and soil moisture while increasing reservoir evaporation rates and the amount of water needed by plants and animals. More frequent and severe wildfires are also already occurring along with post fire flooding that triggers heavy debris flow and erosion.

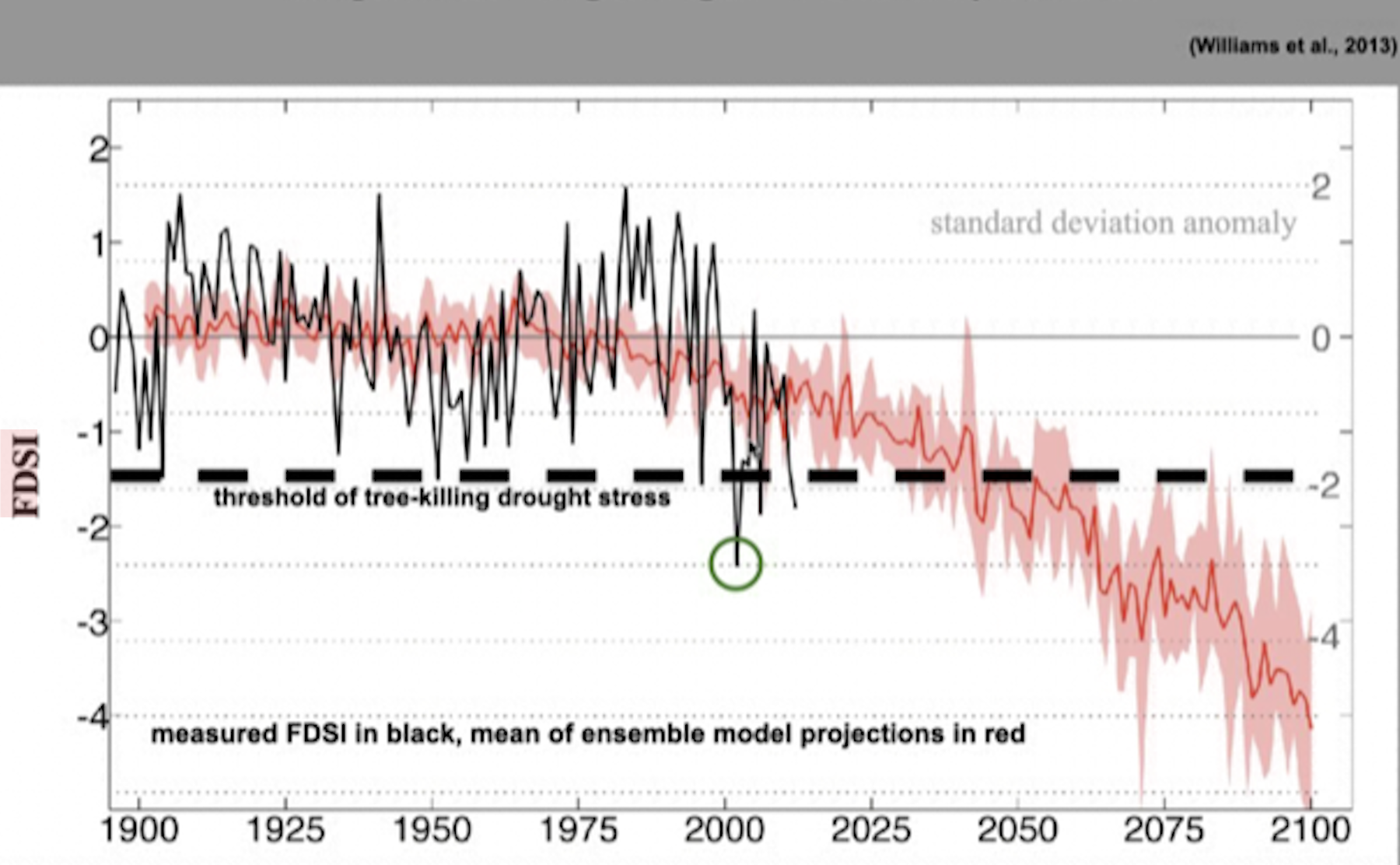

It is anticipated that south-facing slopes will lose soils that take 1,000 years to form. In northwest New Mexico, the loss of vegetation that holds sand dunes in place will result in sand migration covering roads and homes. Eastern New Mexico will experience the return to dust bowl conditions. Some forests will disappear; some shorter forests may evolve. In 1,200 years of tree ring data we are currently experiencing the worst “megadrought.” Several climate models project the threshold for tree-killing drought will be met before 2050. Videos of scientists’s presentations.

Rising Temperatures

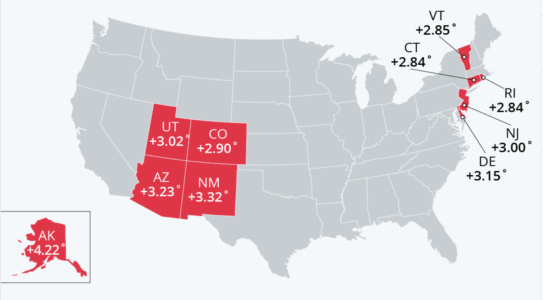

After Alaska, the southwest is the fastest warming part of the country, and New Mexico has warmed the most of these states, rising 3.32°F between 1970-2018. Las Cruces, NM was the fastest warming city in this report. (Climate Central)

Reduced SnowPack and Stream Falls

Reduced SnowPack and Stream Falls

Shrunken snowpacks and earlier snowmelts contribute to lower stream flows at critical times of year when the reduced availability of water has greater economic and environmental consequences.

Low Reservoirs

Elephant Butte Reservoir reached its lowest level in 40 years in 2013—just 3 percent of its storage capacity, compared with a nearly full reservoir in 1994 (left). As a result, farmers received less than 10 percent of their typical irrigation water, forcing them to turn to groundwater and other sources. To see the latest levels click here.

Low Flow in the Rio Grande

Low Flow in the Rio Grande

Flow in the Rio Grande, which relates directly to the amount and timing of snow melt in the mountains north of Albuquerque, is one of the best indicators of drought in New Mexico. Every year from 2009 to 2014 was drier than average on New Mexico’s portion of the Rio Grande, and the period from 2011 to 2013 was the hottest and driest since recordkeeping began in 1895 (Cart 2013). And in southern New Mexico, the Rio Grande stands dry for up to nine months of the year. (New Mexico in Depth). To see a graph of the last 5 years of Rio Grande stream flow at one point click here.

In a 2018 paper from University of New Mexico graduate Shaleene Chavarria and UNM’s Earth and Planetary Sciences Professor, New Mexico’s leading climate scientist, David Gutzler, show how warming is affecting snowpack and streamflows. New Mexico in Focus PBS Video

Rainfall, when it occurs, tends to happen in more extreme deluges, leading to flooding. And the timing of precipitation over the course of the year is shifting, creating mismatches between water supply and water demand, especially for agriculture. Across the Southwest, the capacity of snow to store water is crucial to managing water, and climate change risks disrupting this vital source of New Mexico’s water supply. Click on the image to get the latest drought statistics.

Increased Wildfires

In recent years, drought, insects, and wildfires have ravaged New Mexico forests at a scale not seen in living memory. Higher temperatures and drought will increase the severity, frequency and the extent of wildfires in New Mexico. These wildfires have the potential to cause destruction to property, livelihoods, and human health. The smoke created by wildfires can reduce air quality and increase medical visits for chest pains, respiratory problems, and heart problems. Las Conchas Fire, Los Alamos, 2011. Click on the image to get the most recent wildfire statistics for New Mexico.

Cultural Heritage

Extreme precipitation, flooding, and wildfires have affected sites that are central to New Mexico’s heritage. The rock carvings and cliff dwellings of Bandelier National Monument tell the story of some of the earliest inhabitants of the Americas, while their descendants live nearby in modern-day pueblos. Protecting the archaeological, ecological, and cultural features of this landscape has become more difficult as drought, large wildfires, and extreme flooding increase the risks to them and the infrastructure they depend upon.

Learn More:

Land Witness Project

From ranchers to rafting guides, New Mexicans share their stories of how climate change is affecting their lives and livelihoods. These stories seek to deepen scientific understanding of what is at stake for us as individuals and communities in New Mexico. They illuminate climate change-related dangers and opportunities for ordinary New Mexicans to take action right now to protect our home.

Our Land, PBS New Mexico

Our Land, PBS New Mexico

Our Land has weekly episodes on climate issues in New Mexico. There are interviews with leading climate scientists, Rio Grande Water issues, and community gardens. All shows are archived.

Confronting Climate Change in New Mexico

Confronting Climate Change in New Mexico

New Mexico’s climate is getting hotter and drier, driven by regional and global warming trends. This means earlier springs, hotter summers, and less predictable winters. Precipitation patterns are also changing, with more intense droughts and a greater proportion of precipitation falling as rain rather than snow. Shrunken snowpacks and earlier snowmelts contribute to lower stream flows at critical times of the year when the reduced availability of water has greater economic and environmental consequences.

New Mexico at Risk

New Mexico at Risk

States At Risk Project for visualizing climate change.

Vulnerable to Climate Change, New Mexicans understand its risks

Vulnerable to Climate Change, New Mexicans understand its risks

Laura Paskus, NM political report 2017

Most New Mexicans know climate change is happening and understand it is human-caused. According to recently-released data, New Mexicans are also more likely than people in about half the country to talk not just about the weather, but climate.